An Amsterdam Case-Study

1. Chinatown: Going Transnational

Throughout the 20th century, the concept of ‘Chinatown’ has not failed to stir our imaginations. Many books and films evolve around this part of the city, whether the city is New York, London, Vancouver or Amsterdam. When entering ‘Chinatown’, we always know where we are; it is a clearly defined space within the urban scenery.

A part of what makes the space of ‘Chinatown’ so appealing is the fact that it is filled with contradictions. It is a private space that belongs to the Chinese immigrants of a city, yet it is also a public space that attracts many tourists and urban consumers. It is supposedly a dark, mysterious space that is a breeding place for crime and gambling. But on the other hand, we know it as a colourful, lively place where shops and restaurants have been flourishing for decennia. It is a Chinese place, yet it is situated in the hearts of many Western modern cities, which ultimately also makes it a ‘Western’ concept.

Chinese have crossed borders and started to form little districts that go beyond the context of their origin. Here I will explore this idea of Chinatown. What kind of space is ‘Chinatown’? What is its origin? Is it still authentic in the way that it is indeed a part of ‘China’, or has it been ‘Disneyfied’ into an artificial part of town to please local consumers? The red thread is the journey of ‘Chinatown’ from its coming into being until its presence in the current international urban scene and its place in the world today.

Chinatown Amsterdam will function as a case study here. Having worked as a guide in the old city centre of Amsterdam for over eight years, this is the Chinatown that I know and have experienced most. Firstly, I will explore the historical origins of present-day Chinatown. I will explain what I mean by ‘Disneyfication’ and ‘authenticity’. In the second part I will discuss the current space of Chinatown in the city of Amsterdam. In the third part, ‘Beyond China’, I will elaborate on what the idea of ‘Chinatown’ actually means.

The Concept of Chinatown

The Chinatown of Amsterdam is a case study in this essay. The fact that it is a ‘case study’ is because ‘Chinatown’ actually can be seen as a universal concept. According to the dictionary definition, a ‘Chinatown’ is a district of any non-Chinese town, especially a city or seaport, in which the population is predominantly of Chinese origin. Crissman (1967) speaks of a common structure that makes it possible to describe urban Chinese societies throughout South-East Asia, America or Europe, in terms of the same model. It is possible to discern a similar segmentary organisation underlying the superficially different characteristics of diverse communities.

The term ‘transnationalism’ in this context is coined by Benton and Gomez in Chinatown and Transnationalism (1998). Whilst ‘international’ refers to that which is carried on between nations, ‘transnational’ refers to that which is extending or operating across national boundaries. The term is used in this context since Chinese immigrants in ‘Chinatowns’ develop and maintain multiple relationships, whether it be familial, economic or social, that reach across borders (Benton & Gomez 1998, 6). The concept of transnationalism might, however, not be sufficient anymore to capture modern-day Chinatowns, since it implies identification with the ‘homeland’ and second or third generation overseas Chinese do not all feel this identification anymore. However, as Benton and Gomez say:

In its currently accepted definition, a transnational community is a social formation best exemplified by ethnic diasporas. It relates in the manner of a triad to its globally dispersed self, the states it inhabits, and its ancestral homeland. Its medium is the network, dynamised by new technologies. Multiple identifications and a cultural fluidity (…) mark its “consciousness” (1998, 6).

In this way, we can think of ‘Chinatown’ as a transnational community.

Chinatowns over the globe share a certain common structure. According to Crissman (1967), this is an indication that the social organization of ‘Chinatown’ did not originate abroad, but rather derived from patterns indigenous to China itself. Main characteristics of Chinese communities of ‘Chinatowns’ are that they stand apart from the rest of the population, and that the affairs of any group of Chinese are likely to be of concern to all the Chinese living there. It is not a homogenous group. Rather, it exists out of sub-communities that are entwined and overlap. Sub-communities are based on a shared native place in China, a shared language, or a shared name.

Large-scale Chinese migration started around the middle of the 19th century. The greatest part of emigrated Chinese come from Guangdong and Fujian. The ethnic categories within this group of immigrants vary from Hainanese to Cantonese and from Hakka to Hokkien. New immigrants usually followed the footsteps of friends or relatives who preceded them, and took on the same occupations. As a result, many immigrants with the same profession also had the same native place. Until the First World War, there were hardly any women immigrants from China, as it was the men who first went abroad out of economic necessity to test the waters (Crissman 1967).

While Crissman explains Chinatown in terms of ethnicity, Kay Anderson (1987) finds this problematic, as he argues that race, just as the whole concept of ‘Chinatown’, is an idea that belongs to the “white” European cultural tradition. He sees Chinatown as a “victimized colony” of the East in the West (1987, 580). As he says:

“Chinatown” is not “Chinatown” only because the “Chinese”, whether by choice or constraint live there. Rather, one might argue that Chinatown is a social construction with a cultural history and a tradition of imagery and institutional practice that has given it a cognitive and material reality in and for the West (1987, 581).

Anderson refers to Chinatown as an “imaginative geography” as in Edward Said’s “Orient”; it is an arbitrary classification of space and a regionalization that belongs to Western society and derives from generalizations about the world’s different populations. There has, after all, never been an ‘Anglo town’- so why has ‘Chinatown’ as a category been approved by governments? Anderson describes how ‘Chinatown’ was listed as a separate category in the city of Vancouver in 1900 in health committee reports. ‘Chinatown’ and ‘unsanitary’ were concepts that went hand in hand. The Chinese were fundamentally set apart through the way in which ‘Chinatown’ was imagined and associated with uncleanliness, lawlessness and evil.

Anderson and Crissman seem to contradict each other in many ways. However, they both assume that there is some universality to the concept of ‘Chinatown’; Anderson finds this in the way ‘Chinatown’ is a made-up concept from outside, Crissman finds it in the way ‘Chinatown’ is constructed from within.

Authenticity & Disneyfication

I will explore the space of ‘Chinatown’ by using the concepts of authenticity and Disneyfication. I will explain here what is meant by these terms.

In ‘Changing Landscapes of Power: Opulence and the Urge for Authenticity’ (2009), Zukin states that authenticity has several virtues as an analytical construct.It directs attention to culture as well as political economy in the development of global urbanism. ‘Authenticity’ connects to the modern search of ‘real’ identity (Zukin 2009, 543); in rapidly changing and globalizing urbanity, there is a growing search for what is authentic. Authenticity, however, is an ambiguous concept. On the one hand it represents something that is almost mystical, that has its origin in both time and space. But on the other hand it is often used for something that is new or creative. Zukin mentions how ‘authenticity’ can be used as a substitute for Lefebvre’s ‘Espace Veçu’.

The main idea of Lefebvre’s The Production of Space is that space is a social product. He uses three ‘tools’ to analyse historical notions of space. These three aspects are explained in different ways. ‘Le Perçu’, the perceived space, is the materiality of space. ‘Le Conçu’ is the conceived space; the professional and theoretical way in which space is planned by, for example, urban planners and cartographers. Lastly, ‘Le Veçu’, the lived space, is the one that can be used to understand ‘authenticity’. ‘Lived space’ is the emotional experience of space that develops through the imaginary and through lived experience of the first two spaces. It is a set of social practices attached to existing buildings or land, and it is the metaphorical framework that gives the right to a certain vulnerable population to make their own urban space (Hubbard et al 2004; Zukin 2009).

Because there are many new forms of mobility, and technology is progressing rapidly, there is often talk of cities losing their ‘soul’. People are less attached to places than they were before, but more so in search of that which is authentic. A search for authenticity in a way is a search for identity. Authenticity gathers people together in collectives that are felt to be real; providing meaning, unity and a sense of belonging (Lindholm 2008). In characterizing something as ‘authentic’, both origin and content play a big role; both the historical and identity aspect. Authenticity stands in contrast with that which is not real: that which is fake or unreal.

This leads me to the next term: ‘Disneyfication’. I use this term here since I feel it is applicable to the space of ‘Chinatown’, and since it contrasts with the concept of ‘authenticity’. The term ‘Disneyfication’ is coined by David Damrosch in his What is World Literature? (2003) when he speaks of globalization and world literature. He uses this term to acknowledge the problem that many foreign works of literature will only be translated and distributed to the West when its content ‘fits’ the image we have of that certain culture. As a result, many foreign authors already write in a way that will get them publicized in the West. What remains is in fact a ‘fake’ type of literature: books that hold up certain stereotypes in order to please the “West”. This is the same as what happens in Disney’s Epcot Centre. The Epcot Centre is an amusement park that is part of Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando. In this theme park you have the so-called ‘World Showcase’ where you can visit tiny versions of the world’s countries, varying from Turkey to China, with attractions that go with it and that portray a multitude of stereotypes and cliché’s about the corresponding cultures. I apply the concept of ‘Disneyfication’ to Chinatown since the same might be happening in Chinatowns over the world; the Chinese community and their space are portrayed as exotic and exciting, but in way that you could call ‘market realistic’: consumers can come and spend an afternoon in a ‘real’ Chinese teahouse, that has, in fact, nothing to do anymore with ‘authentic’ Chinese culture. Through globalization and Disneyfication, other cultures come in packages that are accessible and ready for consumption.

I will now return to Amsterdam, and the origins of this capital’s ‘Chinatown’.

2. Chinatown and the City

The Chinese of Amsterdam

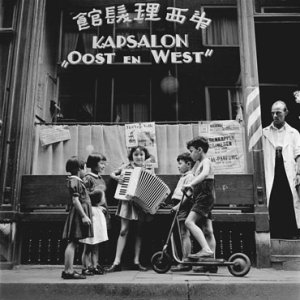

Origins of the Chinese are so diverse that it is actually impossible to speak about a homogeneous group. This is also reflected in the Chinese immigrants in the Netherlands. The first Chinese already came to Holland at the end of the 19th century on ships that sailed between Europe and the Dutch East Indies. The first big wave of Chinese immigrants came in 1911, when Dutch shipping companies brought them over from England in order to break the big strike of Dutch sailors. These Chinese, from Guangdong, were the first ones to settle down Holland (Benton & Vermeulen 1987). Later on, immigrants from, amongst others, Zhejiang and Shandong also followed in their footsteps. Although the majority initially settled down in the seaport of Rotterdam, Amsterdam later on became the primary settlement for Chinese immigrants. In the 1930s they became a well-known phenomenon in the street image of Amsterdam as peanut-sellers. They primarily settled in the area around the Binnen Bantammerstraat and Zeedijk. In De Chinezen van Amsterdam [‘The Chinese of Amsterdam’] (1966), Vellinga and Wolters describe how this neighbourhood was characterized by the presence of the Chinese and their restaurants and boarding houses. The many Chinese characters on the windows and the people who sat outside their shops on warm days gave the whole area a sense of the East. They use a quote from an American book on Chinese communities to illustrate the overall atmosphere of this neighbourhood in the 1960s:

These restaurants in ‘China-town’ cater to Chinese customers and to the general American public who enjoys a China-town week-end adventure, not only to eat ‘chop suey’ and ‘chow mein’ but also to watch the yellow ‘Chinaman’ talk and eat and to breath an atmosphere pervaded by Oriental color, sound and symbolism (Vellinga & Wolters 1966, 1).

Although Vellinga and Wolters make the Chinese neighbourhood of Amsterdam seem like a harmonious place, the background of the district is less charming. Around 1918, the Dutch government referred to the area around the Binnen Bantammerstraat as a ‘Chinese colony’. Even though a lot of the literature on ‘Chinatown’ make it seem like the Chinese somehow naturally ‘settled down’ there, it was actually the Dutch who confined them to the area around the Nieuwmarkt and Binnen Bantammerstraat, since the boarding houses of the Chinese were set up there. The Chinese were brought over to break the big seamen strike, but in the end they were not needed for that. Shipping companies kept the Chinese ‘on hold’ in the boarding houses since they were cheap workers. While many Chinese seamen were waiting for a next possible embarkation, they camped in Amsterdam’s boarding houses. Shipping companies started to hire the Chinese as stokers on their ships; with temperatures over fifty degrees they worked more than twelve hours a day. They got paid 80 to 100 guilders per month. Although they only got 70 percent of what a Dutch sailor would get paid, 90 percent of their earnings went to the shipping master, who was also the holder of the boarding house. Exploited, and without legal status or support, the Chinese were living in Amsterdam in hunger. When the technology of ships advanced, and stokers became redundant, many Chinese had bleak prospects. The economical crisis of the thirties, the Second World War, and new registration procedures implemented by the government left them unable to return to their homeland. Next to selling peanuts, smuggling opium and weapons was a much needed source of income to them (Heek 1936; Zeven 1987; Sanders 2008).

In 1928 the first Chinese restaurant of Amsterdam was established in the Binnen Bantammerstraat. After the Second World War, more of them opened for business. Of the approximately 3000 Chinese in Rotterdam and Amsterdam before the war, only ten of them were women. After the war more women joined the Chinese community (Chong 2005). In 1966, the time when Vellinga and Wolters wrote their work on the Chinese, there were 83 Chinese restaurants in Amsterdam. The Chinese started to flourish as entrepreneurs while the Binnen Bantammerstraat remained the centre of the Chinese in the Netherlands. Apart from the restaurants, it was also home to gambling houses and opium dens. While the ‘old fashioned’ Chinese community continued to exist, new problems rapidly emerged in the 1970s and 1980s: heroine was introduced in Amsterdam (Sanders 2008). As Suriname gained independence in 1975, many Surinams came to Amsterdam looking for work and money, and became dealers of drugs for Chinese people who used the trade of opium, heroin and weapons as their extra source of income. As the area around the Zeedijk became a no-go area, the Dutch government gained more access to the closed world of ‘Chinatown’, which fascinated outsiders enormously. This led to regular reports on the Chinese community appearing in the press.

Sanders (2008) comments how mayor Nico Polak in 1966 produced a two page long reportage about the Binnen Bantammerstraat from which the following quote gives an impression:

Question 3: which typical Chinese institutions can be found in the Binnen Bantammerstraat and its surroundings? Answer: Eight Chinese restaurants for Dutch people, four gambling houses, two opium dens, several boarding houses, three unique neighbourhood cafes, a hairdresser specialising in Chinese hairstyles, two Indonesian grocers, three clubhouses for various groups of Chinese and four Chinese restaurants for Chinese people (Sanders 2008).

The problems on the Binnen Bantammerstraat and Zeedijk made the Dutch realize how closed and unknown ‘Chinatown’ actually was to them. In Bureau Warmoesstraat (2000) Koring describes how local police noticed a change taking place in the normally ‘peaceful’ Chinese community. They discovered brown chunks that resembled brown sugar. It was called the ‘white death’ by the Chinese: heroin. Although some officers discovered the existence of triads, nobody would believe them when speaking of the presence of ‘secret gangs’ on the Zeedijk and Binnen Bantammerstraat (Koring 2000: 121). It was eventually the American Drugs Enforcement Agency who helped Amsterdam unravel the world behind the restaurants; three triads, named 14K, Wo Lee Kwan, and Wo Sing Wo, were battling over the heroine that came into Amsterdam. Because of these investigations it became clear that the Chinese community in Amsterdam consisted of about 5000 people. Chung Mon, leader of the 14K, played an important role in this community. He seemingly only owned a restaurant, a gambling house and a travel agency. In fact he controlled the whole trade of heroine that went in and through Amsterdam. When he was killed in 1975, his influence became very clear through the amount of Chinese that participated in his funeral. Thousands of Chinese from the whole of Europe came to pay him their last respects. To end the triads, the Dutch police started to check up on Chinese gambling houses and restaurants on a daily basis, and deported those who were illegal in Holland (De Vries 1985).

Present-day Amsterdam ‘Chinatown’ consists of restaurants, shops, bars, and a Buddhist temple that was opened by Queen Beatrix in 2000. In 2006, the local government placed Chinese street signs on, amongst others, the Zeedijk, Stormsteeg, Binnen Bantammerstraat and Nieuwmarkt. ‘Chinatown’ is named as an official district on both the websites of Amsterdam City Council as that of NV Zeedijk[1]. The NV Zeedijk promotes ‘Chinatown’ on its website:

A visitor to Amsterdam Chinatown cannot only enjoy Chinese cuisine, but can also pay a visit to one of the supermarkets where you can find authentic Oriental products (…). The typical oriential atmosphere makes you feel like you are in China (NV Zeedijk).

The local government, NV Zeedijk and the Chinese Association work together to maintain Amsterdam’s ‘Chinatown’, which organizes events like the Chinese Newyear. An Amsterdam City Council’s report dating from 2007 speaks about the future of the city’s district. The report states that ‘Chinatown’ is an important point on Amsterdam’s agenda. It says: “The development of Chinatown has always had a prominent spot in the City Council, and the city district of Amsterdam-Central has, in order to promote this idea, even placed Chinese street signs over a year ago” (Alkema 2007). The City Council states that they worry about Chinese enterprises moving out of the district due to a lack of parking spots, nuisances by the presence of drug addicts and troubles in acquiring permits for their businesses. Non-Chinese take the places of those moving out of the district, and new Chinese hubs that are opening in Beverwijk and near Schiphol Airport ‘endanger’ the future of Amsterdam’s Chinatown. The report predicts that if Amsterdam ‘Chinatown’ offers visitors a theme hotel and restaurants that fit the image of the temple, it will attract more Chinese businessmen and tourists (Alkema 2007).

Space and the City

Debates on space and place are countless and diverse, and are connected with social, economic and political phenomena. It was the Marxist theorist Henri Lefebvre who convincingly articulated ‘space’ as socially produced. Lefebvre’s theory states that there is no absolute space. The moment a space is taken over by social activity, it becomes dependent of this and is historicized because of it (Hubbard et al 2004). Societies, communities, modes of production; they all produce their own space. Whilst rejecting the existence of absolute space, Lefebvre introduces the trialectics of space as ‘perceived’, ‘conceived’ and ‘lived’, as introduced before. The lived experiences of people define the type of space.

Lefebvre elaborates on the question: what is the ‘urban’? He discusses that the urban, the city, is not about population, size or buildings; rather it is a combination of all of these things together as a form. Elements and aspects of capitalism crisscross in space. Geographical space is always ‘spatialized’ by capitalist societies; ‘space’ is consistently owned by someone (Hubbard et al 2004: 210). Lefebvre, however, speaks of a ‘right to the city’: a city is the gathering and dispersing of goods, information and people. The city belongs to everyone. By ‘thinking’ the city in this way, Lefebvre takes us away from the notion that space is something that can be planned or touched. It rather is a historical notion that is lived, and then also imagined. It is this ‘lived space’ that attracts, for example, artists and painters. It lives in the images of people.

When we take a walk from Amsterdam Central Station to the beginning of the Zeedijk, about fifteen minutes, there is a change of atmosphere. The beginning of the Zeedijk is characterized by small café’s, some of which have been around since the 16th century. People who have been living on the Zeedijk for a long time gather in these small bars, from ‘In ‘t Aepjen’, ‘De Kletskop’, to ‘De Ooievaar’. These bars pour Amsterdam liquor and beer, and most bar-owners have been around for years. From the beginning of the Zeedijk you pass by several gay bars and a few minutes later you step into an area we now know as ‘Chinatown’. The change of atmosphere is noticeable in the Chinese characters on the windows of copy-shops, massage parlours, and Chinese pharmacies. Restaurants that sell Peking duck attract large groups of Chinese customers. Outside the temple there are monks who walk among tourists. Immediately you know: you have stepped into an area that is somehow different from the first part of the Zeedijk, although there are no clear boundaries of where it starts or where it ends.

The space of Amsterdam’s Chinatown means something different to different people. It is a rapprochement between physical space, mental space and social space. Lefebvre stresses that the realms of perception, symbolism and imagination are not separable from physical and social space (Merrifield 1993). Especially imagination plays an important part in considering the space of ‘Chinatown’, since it is not a typically ‘Dutch’ part of the city of Amsterdam, like the Jordaan or de Pijp; the aspect of the different (Chinese) culture is what characterizes this district. It is also this culture aspect that is spatial.

It is Homi Bhabha who has become particularly well-known because of his work on space and culture. For Bhabha, culture is primarily spatial. A cultural space is the location of shared practices. This space, as Lefebvre also indicates, is generated in response to particular historical and geographical conditions; yet, it cannot be simply said to belong to one specific culture or another (Hubbard et al 2004). Bhabha therefore speaks of a ‘third space’. In Bhabha’s terms, ‘Chinatown’ can also be approached as a ‘third space’. The identity of the space of Amsterdam’s Chinatown is not authentically Chinese, nor authentically Dutch. It is both Chinese and Dutch, and at the same time neither Chinese nor Dutch. Terms of cultural engagement, according to Bhabha, are produced performatively. The representation of difference must not be read as the reflection of pre-given ethnic or cultural traits (Bhabha 1994). This is quite problematic, as Bhabha indicates by citing Renée Green: “Even then, it’s still a struggle for power between various groups within ethnic groups about what’s being said and who’s saying what, who’s representing who? What is a community anyway? What is a black community? What is a Latino community?” (Bhabha 1994: 3). In the same way we can wonder: what actually is a Chinatown? What actually is a Chinese community?

Sticking to Bhabha’s terms, we could call the space of Chinatown a space of ‘in-between-ness’ (Bhabha 1994). The space of Chinatown is not only generated by its history or geographical place. There is more than that. It is precisely this ‘more’ that is ‘in-between’. Bhabha urges for a nuanced reading of cultural identities within the geographies of migration and diaspora. Displaced populations face complex dynamics of negotiation that are accompanied by forced stereotypes. They live their lives across contesting cultural values and traditions. More than a cultural space, it signals a process of “cultural translation” between traditions (Hubbard et al 2004: 54). Bigger cities of the world, that do not only have Chinese, but also Latino or Muslim immigrants, all deal with urban spaces like this.

3. Beyond China

An Imagined Space

Lefebvre speaks of space as possibly ‘lived’ in the minds of people. Bhabha articulates both a ‘third space’ as an ‘in-between-ness’. In my view, these notions can all be connected with Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities (1983). In his book, Anderson shows how the world is made up of “imagined communities” that we call nations. It is imagined because the members of a nation, whether big or small, will never know or meet most of the members, nor hear from them, yet still in their minds they have the idea that they somehow belong together. Anderson indicates that notions like nation, nationality and nationalism are very powerful concepts. Even so, the scholarship on it has been quite poor.

Although Anderson mainly focuses on nations, his idea is also applicable to communities within the urban scenery that are based on a sense of nationalism, like ‘Chinatown’. As indicated earlier, it is hardly possible to speak of a homogenous community when speaking of the Chinese in Amsterdam. Although backgrounds may vary, there is still a sense of the ‘Chinese community’ in Amsterdam, as also becomes clear through organisations that connect the community, like the Organisation of Chinese Entrepreneurs (阿姆斯特丹华商会). Chinese organizations, shared festivities, and gathering places like the temple or community centre, all help in the process of ‘thinking’ the community. The space of Chinatown is generated, in Lefebvre’s terms, by its ‘lived space’, its social activities. The ‘imagined’ aspect of the community becomes especially clear when noticing that third-generation Chinese, who may have a Dutch lineage, are still part of this community. The people of ‘Chinatown’, according to Bhabha’s words, are neither Dutch nor Chinese. They are beyond China. They are in an ‘in-between-ness’ that, by Andersons notion, is ‘imagined’.

Speaking of ‘imagined’ by no means indicates a sense of falseness. It does not contradict with communities that are somehow ‘unimagined’. It is rather an indication of the way in which a community is constructed from popular processes through which residents share nationality in common. As Hubbard (2004) points out, this understanding both shapes and is shaped by political and cultural institutions as people imagine they share general beliefs and attitudes, while recognizing a collective national public as having similar sentiments to their own (17).

There is, however, an important critique when applying Anderson’s notions of imagining communities to ‘Chinatown’. As Partha Chatterjee (1993) points out, the imagination of political communities has been limited by European colonialism. When speaking earlier of pre-war ‘Chinatown’ as small ‘colonies’, this could also be applied to the district. When Amsterdam’s Chinatown was established at the beginning of the 19th century, specific institutional forms were imposed upon the Chinese immigrants by the way they were put into boarding houses and were denied some legal rights the Dutch had. Since their independence was limited, they had no option but to follow the path Amsterdam laid out for them. As Hubbard quotes Chatterjee: “Even our imaginations (..) must remain forever colonized” (2004, 19).

Chinatown: Authentic or Disneyfied?

In the light of Imagined Communities, I will now return to the concepts of ‘authenticity’ and ‘Disneyfication’. Because, what is ‘Chinatown’? Whose ‘town’ is it, anyway? As indicated before, authenticity gathers people together in collectives that are felt to be real and provide meaning, unity and a sense of belonging. After reviewing both Benedict Anderson (1983) and Kay Anderson (1987) it becomes clear that the approach to what ‘Chinatown’ actually is, is multi-layered.

‘Chinatown’ is an authentic ‘space’ in the sense that it gathers the Chinese community. It is a place that, historically, bounds them, even if they live in other parts of the Netherlands. The Amsterdam Chinatown, like others in Europe, has long ceased to be a ghetto of overseas Chinese. Chinatown is rather a service centre that also serves as a venue for major community events. Even if it is not the real ‘ghetto’ anymore, it might be called an ‘imaginary ghetto’ as Flemming (1998) puts it, since an image of Chinatown at odds with the reality of geographical dispersion still manages to fill the community’s members with a sense of belonging. This is in accordance with what Benedict Anderson says about “imagined communities”, with what Lefebvre calls ‘lived space’, and with what Zukin (2009) calls ‘authentic’; a mythical concept that originates in both time and space.

The fact that we could call ‘Chinatown’ an ‘authentic’ place, however, does not mean that it is in no way ‘Disneyfied’. This is something that makes the concept of Chinatown multi-layered. It is not only an “imagined community” from the ‘inside’, which is, in the way the Chinese community ‘thinks’ the community; it is also an “imagined community” from the ‘outside’, which is, in the way the nation (here: Holland) ‘thinks’ the space of ‘Chinatown’. This is also exemplified in the way Kay Anderson illustrates the construct of Vancouver’s Chinatown. He states that ‘Chinatown’ is a social construct that belongs to the “white” European society. He is correct in critiquing the ways in which many academic works naturally state that Chinese immigrants established Chinatowns themselves. When looking at Amsterdam, it becomes obvious that the settlement of Chinatowns was not so ‘natural’ at all; an aspect that is also confirmed in the way Chatterjee (1993) critiques Benedict Anderson: not all communities naturally ‘imagined’ themselves.

The ‘Disneyfication’ of ‘Chinatown’ also becomes clear through the reports of the local government on this district. The report by Alkema (2007) talks of promoting the “idea” of ‘Chinatown’. This “idea” does not belong to the Chinese community, but to the Amsterdam government, who believe that by placing Chinese street signs and building ‘theme hotels’ the “idea” of ‘Chinatown’ can be further developed. A ‘Disneyfication’ of Chinatown is believed to attract more tourists and visitors who want to enjoy a sense of the ‘Orient’ for an afternoon.

There is no judgement in speaking of the way in which both local governments as Chinese communities imagine their ‘Chinatown’. Both authentic and Disneyfied, ‘Chinatown’ is an imaged space on different levels. The greatest challenge for the district lies in its past and in its future: to find a balance in who is dominant in the way the district is envisioned.

I explored the space of ‘Chinatown’, a place that is filled with contradictions that are visible on a superficial level and is multi-layered on the underlying level as well. It is ‘Chinese’ and ‘Dutch’. It is universal and local; transnational and national. It is private and public. It is authentic and Disneyfied. The contradictions of the space of ‘Chinatown’ poses some challenges. These challenges of ‘Chinatown’ can be faced by acknowledging the ‘in-between’ aspect of the space. Through collaborating and negotiating, sacrifice and consent, Chinese organisations and the local government can, and hopefully, will, find a way to make ‘Chinatown’ a space that all parties feel comfortable “imagining”. Just as the city belongs to all of us, ‘Chinatown’ will then be a space that, likewise, belongs to all of us.

References

Alkema, Yellie. 2007. Publicaties Stadsdeelbestuur 2007 (June 28). Amsterdam: Gemeente Amsterdam Stadsdeel Centrum.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities. London: Verso.

Anderson, Kay J. 1987. The Idea of Chinatown. In: Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77 (4): 580-598.

Benton, George and Pieke, Frank (eds.). 1998. The Chinese in Europe. London: MacMillan Press.

Benton, George and Gomez, Edmund Terence. 1998. Chinatown and Transnationalism. Canberra: Centre for the Study of the Chinese Southern Chinese Diaspora.

Benton, George and Vermeulen, Hans. 1987. De Chinezen. Muiderberg: Couninho.

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. Introduction: Locations of Culture. In: The Location of Culture, Homi K. Bhabha, 1-18. London: Routledge.

Chong, Yocklang. 2005. De Chinezen van de Binnen Bantammerstraat, een Geschiedenis van Drie Generaties. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis.

Crissman, Lawrence W. 1967. The Segmentary Structure of Urban Overseas Chinese Communities. Man, New Series 2 (2): 185-204.

Damrosch, David. What is World Literature? Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

De Vries, Peter R. 1985. Uit de Dossiers van Commissaris Toorenaar. Amsterdam: Fontein.

Ealham, Chris. 2005. An Imagined Geography: Ideology, Urban Space, and Protest in the Creation of Barcelona’s ‘‘Chinatown’’. IRSH 50: 373-397.

Flemming, Christiansen. 1998. Chinese Identity in Europe. In The Chinese in Europe, Benton, George and Pieke, Frank (eds.). 1998. London: MacMillan Press.

Heek, F. van. 1936. Chineesche Immigranten in Nederland. Amsterdam: N.V. J. Emmering’s Uitgevers Maatschappij.

Hubbard, Phil, Rob Kitchin and Gill Valentine (eds). 2004. Key Thinkers on Space and Place. London: Sage Publications.

Koring, Cees. 2000. Bureau Warmoesstraat. Den Haag: Uitgeverij BzztôH.

Lefebvre. 1991. The Production of Space. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Lindholm, Charles. 2008. Culture and Authenticity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Merrifield, Andrew. 1993. Place & Space: a Lefebvrian reconciliation. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series 18 (4): 516-531.

NV Zeedijk. NV Zeedijk. http://www.nvzeedijk.nl/

Pieke, F.N. De Chinese Gemeenschap van Nederland. Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1982.

Vellinga, M.L. and W.G. Wolters. De Chinezen van Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1966.

Wong, K. Scott. 1995. Chinatown: Conflicting Images, Contested Terrain. MELUS 20 (1): 3-15.

Sanders, Huub. 2008. The Chinese of Amsterdam. International Institute of Social History (February 24), http://www.iisg.nl/collections/chinezen- zeedijk/chinezen.php (Accessed January 10, 2009).

Zeven, Bart. 1987. Balancerend Op de Rand van Nederland. In De Chinezen, ed. George Benton and Hans Vermeulen, 40-65. Muiderberg: Couninho.

Zukin, Sharon. 2009. Changing Landscapes of Power: Opulence and the Urge for Authenticity. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33 (2): 543-54.

[1] An organisation set up by the local government that regulates housing and manages the area around the Zeedijk since 1985.

Photo by ruddy.media on Unsplash